Standing for Our Professions

Why The Future Of Medicine Depends On More Than Metrics And What The Military’s Moral Collapse Can Teach Us About Healthcare Reform.

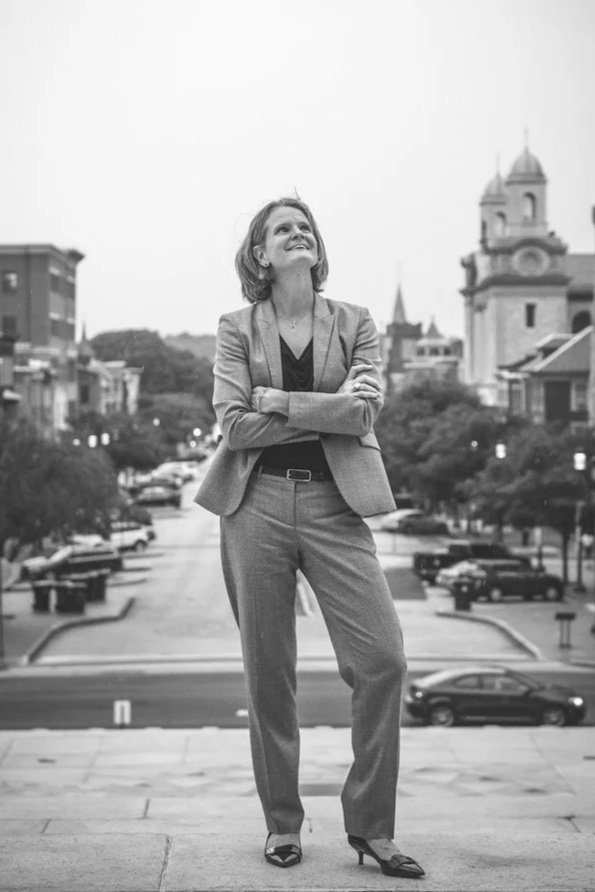

Wendy Dean, M.D., stands on her own square.

Photo credit: Valerie Buller, Rough Coat Photography.

Last month’s post encouraged diplomatic defiance - standing firmly and calmly on our “square” as a place of clarity and safety.

What are we standing for, though?

Is it for patient safety? Professional autonomy? The ability to practice as we were trained to do, for the benefit of those we serve? We believe we are standing for something bigger: the future of medical professions themselves.

What is Medical Professionalism?

Professionalism is a social contract. Medical professionals commit to obtaining the unique knowledge and skills necessary to provide society with the healing and scientific expertise it cannot provide for itself, in exchange for certain privileges - a comfortable living, respect, and self-regulation.

Professionalism is grounded in four pillars:

Technical skills

Human development

Sociopolitical and cultural understanding

Moral and ethical development

These rest on a foundation of accountability, communication, health, and a sustainable professional culture.

Yet, today’s healthcare environment puts each of those principles at risk. Productivity pressure, regulatory constraints, and misaligned goals between health systems and individual practitioners are creating what many experience as an existential threat to healthcare professions. It is a crisis not of exhaustion, but of identity and integrity.

Lessons from the U.S. Military’s Professionalism Crisis

Medicine is not the first profession to face a breakdown in its social contract. Consider the U.S. military in the 1960s.

Robert McNamara, the longest serving US Secretary of Defense (1962-1968), modernized the Army using corporate principles: metrics, efficiency, and central control. His legacy culminated in tragedy. In March 1968, one month after McNamara stepped down, and before his successor had time to reform Army culture, 175 civilians (many of them women, children, and elderly) were killed in the Vietnamese village of My Lai, during a morning raid by U.S. soldiers. Poor intelligence, inexperienced leaders, and a pressure to meet metrics (body counts, in this case) culminated in a catastrophic situation.

Worse yet, leaders claimed the mission had instead killed dozens of enemy Viet Cong fighters. Then a year later, in November 1969, journalist Seymour Hersh exposed the lies, the cover up, and the crumbling coherence of the force. In response, the Army rushed two major inquiries. First, the Peers Inquiry, delivered to Army leadership in March 1970, found that the company in My Lai had “committed individual and group acts of murder and mayhem”, a troubling conclusion to anyone who esteemed the Oath of Office and the Soldier’s Creed.

On receipt of Peers’ report, General William Westmoreland gave the US Army War College three months to investigate how the Army’s command climate may have fostered – or, at very least, did not discourage – such delinquency. General George S. Eckhardt’s findings in the Study on Military Professionalism were sobering. The Army’s fixation on numbers, short command cycles and failure to foster honest communication had created an environment where professionalism collapsed. The soldier “as imagined” by leadership was markedly different from the soldier “as was”, whose behavior was shaped by problematic performance targets. His report catalyzed deep reforms across leadership, ethics training, and internal accountability - prioritizing moral clarity over spreadsheet success. It also set a precedent for regular organizational introspection, reflection, and corrective action.

Medicine’s Crisis Mirrors the Army

In one figure in the Eckhardt report, we see dynamics eerily familiar to healthcare workers today: centralized control, rapid leadership turnover, a preference for metrics over deep expertise, and organizational blindness to both bad news and to long-term consequences. The U.S. Army War College cited these systemic patterns as a root cause of moral failure and a precipitant to tragedy. And now they echo across American healthcare.

Contemporaneously, another cultural shift was underway. In September 1970, economist Milton Friedman argued in The New York Times that a corporation’s only responsibility was to maximize shareholder value. That same year, Jack Welch began rising through the ranks at General Electric. By the 1980s, he had turned GE into a model of efficiency and ruthless bottom-line management.

Welch’s leadership style reshaped business schools, management thinking and, eventually the nonprofit and healthcare sectors. Today’s health systems are heavily consolidated, vertically integrated, remotely managed, and driven by the bottom line, often at the expense of the very people and communities they are meant to serve.

Will Medicine Learn from the Past?

What will be medicine’s “My Lai”? Will we have a moment of reckoning? A ‘Study on Medical Professionalism’?

In 2021, science journalist Ed Yong wrote that health workers could “no longer bridge the gap between the noble ideals of their profession and the realities of its business.” That unbridgeable and untenable gap is the source of moral injury.

Half a century ago, the Army chose reform. It chose to reflect, correct, and reassert its covenant with society. It grounded itself again in ethics, leadership, and human development and rejected productivity, efficiency, and metrics as substitutes for deep, broad expertise.

Will healthcare do the same?

Revitalizing our healthcare professions is an intentional act. We need to stand on our “square” of professionalism, as individuals and together. Speaking with moral clarity and courage, we can lead our professions and our organizations to safer ground – for ourselves, our colleagues, and our patients.